100 years ago, seven men left the Isle of Rona to stake out more fertile land on the Isle of Raasay. They became known as the Raasay Raiders.

It was to Rona – a small, rocky island just north of Raasay – that the Raiders’ ancestors had been cleared to make way for sheep farms during the Highland Clearances.

The Raasay Raiders had warned the Board of Agriculture for Scotland that they were planning to reoccupy their ancestral lands on Raasay to feed their wives and families following World War I.

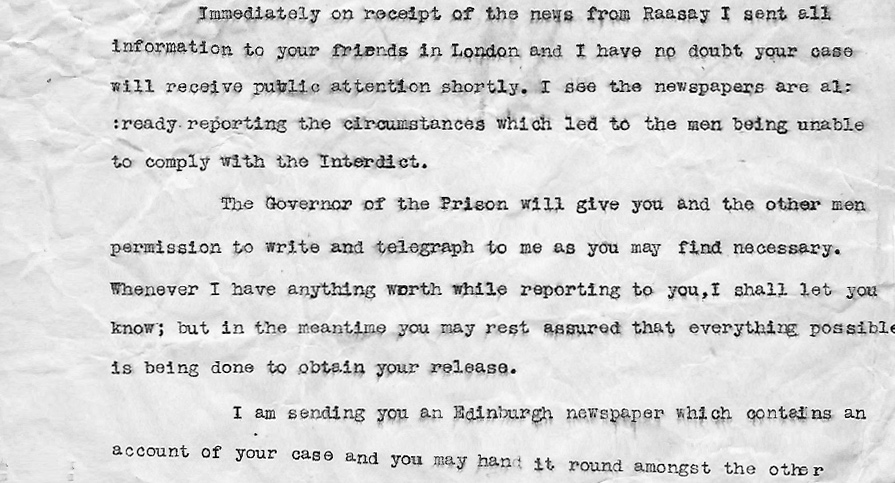

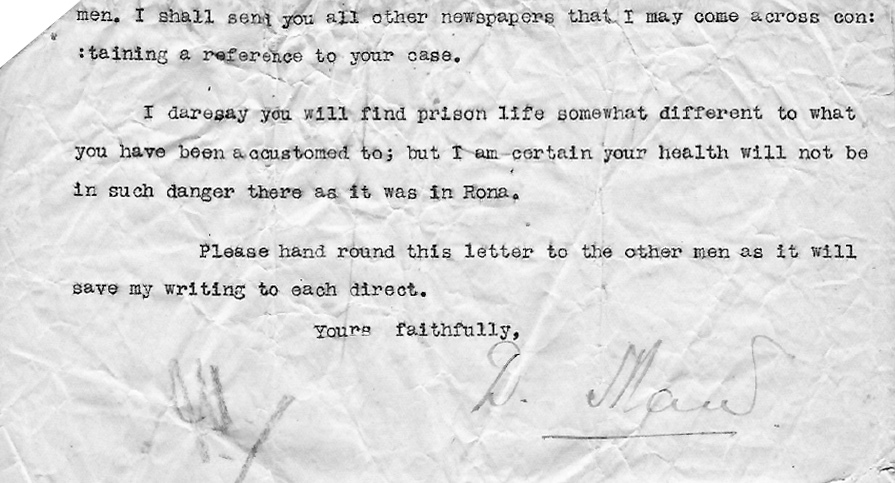

After promises of land in exchange for joining the war effort, the ex-servicemen who made it home began reclaiming the land they fought for, and the land their ancestors had worked for centuries. The seven Raasay Raiders were eventually jailed in Porterfield Prison in Inverness for six weeks and a national public outcry ensued. One of these men was ex-Serviceman Donald Beag MacLeod, grandfather of our Financial Controller Lexy MacLeod and great grandfather of one of our distillers, Duncan Koek.

During the clearances in the mid-19th century, the population of Raasay was halved from over 1,000 to fewer than 600 people. Under the island’s new private landlord, former slave owner George Rainy, the equivalent of the entire population of Raasay today was cleared from the township of Hallaig alone (see Sorley MacLean’s poem, Hallaig).

As well as clearances, according to a government inquiry (The Napier Commission), young couples on Raasay at that time were also forbidden from building new homes or from marrying in order to stop them having children.

At the last census in 2011, the population of Raasay was 161. You might have spotted this number printed on the side of our single malt labels. It represents the Ratharsairich/people of Raasay who keep the Isle of Raasay Single Malt flowing, but sadly also the impact of the Highland Clearances and depopulation on the Highlands and Islands.

James Hunter, the Making of the Crofting Community:

“Several townships in the southern part of that island [Raasay] were converted into a sheep farm and the 63 crofting families who had formerly occupied them were forced either to emigrate to Australia or to remove themselves to other parts of the estate. Raasay’s departing emigrants, one eyewitness recalled, left ‘like lambs separated from their mothers’, and with them, it was reported, they took handfuls of the soil which covered their people’s graves in the island’s churchyard. Those who stayed behind gained none of the land the emigrants had given up. Several families were settled on subdivisions of already meagre holdings. Others were moved to the neighbouring island of Rona, a place that the Scottish Land Court would afterwards describe as ‘suitable for nothing else than grazing for a very limited number of sheep.”

The jailed land raiders were said to have been treated favourably by prison guards who were sympathetic to their cause, being offered ‘corduroy’ in place of the plain white clothing of the other prisoners. Released in December 1921, by 1922, the Department of Agriculture had bought much of Raasay and given each of the raiders a croft – four in Fearns and three in Eyre. Eyre is where there is archeological evidence of a collapsed illicit still from earlier generations.

The legacy of these brave Raasay Raiders is still evident on Raasay. Today, Raasay House, Raasay Hall, and Raasay Community Stores are just some of the assets owned by the people of Raasay. We are proud, as a distillery, to be playing our part creating opportunities to live and work on this thriving whisky and gin producing island today and in the future.